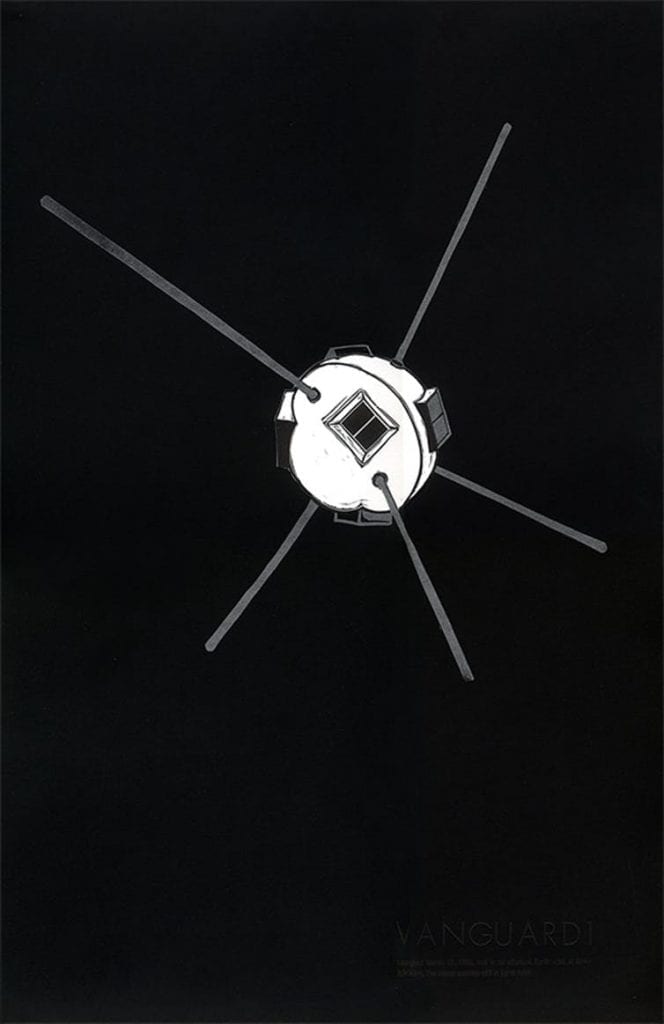

Sixty years ago, a grapefruit-sized aluminium sphere with six antennas and some tiny solar cells was launched into Earth orbit. The Vanguard 1 satellite is still up there and is the oldest human-made object in space. It’s our first piece of space archaeology.

Other early satellites – such as Sputnik 1, the first satellite to leave Earth in 1957, and Explorer 1, the first US satellite – have long since re-entered the atmosphere and burnt up.

Vanguard 1’s legacy, as we enter the seventh decade of space travel, is a new generation of small satellites changing the way we interact with space.

making the first road map for space

By the early 1950s, the second world war’s rocket technology had developed to the point where the first satellite launch was imminent.

The global scientific community had been working towards a massive cooperative effort to study the Earth, called the International Geophysical Year (IGY), to take place in 1957-58. What could be better than measuring the Earth from the outside?

Everything we knew about the space environment we had learned from inside the envelope of the atmosphere. The first satellite could change everything.

The IGY committee decided to add a satellite launch to the program, and the “space race” suddenly became real.

Six nations were predicted to have the capability to launch a satellite. They were the United States, the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom, France, Japan and Australia.

This was before NASA existed. The United Nations space treaties had not yet been written. The IGY was effectively building the first road map for using space.

waging peace in the cold war

Vanguard 1 was intended to make the US the first nation in space – hence its name, meaning “leading the way”. The term also refers to the advance troops of a military attack.

Space exploration was not just about science. It was also about winning hearts and minds. These first satellites were ideological weapons to demonstrate the technological superiority of capitalism – or communism.

The problem was that the IGY was a civilian scientific program, but the rocket programs were military.

Project Vanguard was run by the US Naval Research Laboratory. Public perception was important, and they tried to give the satellite a civilian spin to present the US’s intentions in space as peaceful.

This meant the launch rocket should not be a missile, but a scientific rocket, made for research purposes. Such “sounding rockets” were, however, part of the military programs too – their purpose was to gather information about the little-known upper atmosphere for weapons development.

keep watching the skies!

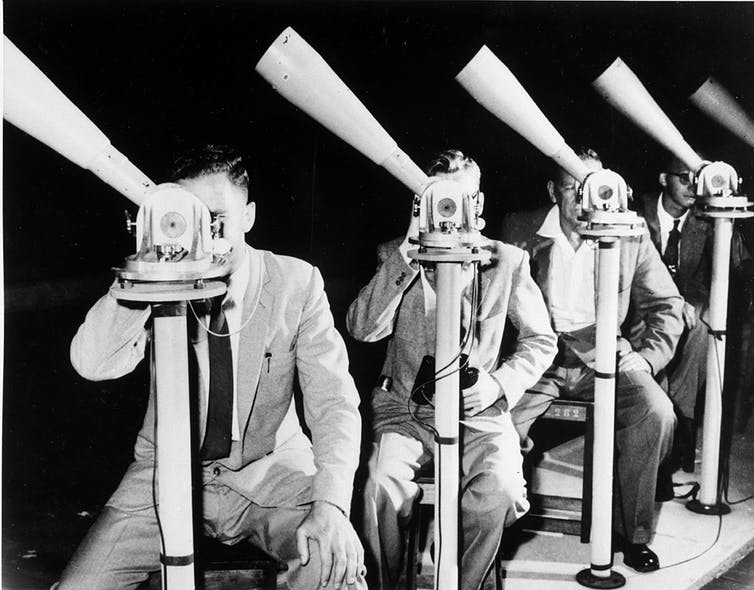

The astronomer Fred Whipple, from the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory, had an idea for the IGY satellite program that would help Project Vanguard present the right image and contribute to the scientific outcomes.

It was all well and good to launch a satellite, but you also had to know where it was in space so that you could collect its data. In the 1950s, the technology to do this was still in its infancy.

And in the words of science fiction author Douglas Adams, space is big. Really big. When something the size of a grapefruit is launched, you can predict where it should end up, but you don’t know if it’s there until you’ve seen it. Someone has to look for it.

This was the purpose of Whipple’s Project Moonwatch. Volunteers – nowadays we would call them citizen scientists – across the globe watched for the satellite using binoculars and telescopes supplied by the Smithsonian. But their first satellite sighting was not Vanguard 1. The Soviet satellite Sputnik 1 became the first human artefact in orbit on October 4, 1957.

vanguard 1’s descendants

Six months later, on March 17, 1958, the little polished sphere was lofted up to a minimum height of around 600km above the Earth, and there it has stayed, long after its batteries died. Technically, Vanguard 1 is space junk; but it doesn’t pose a great collision risk to other satellites. It has survived so long simply because its orbit is higher than the other early satellites.

The historians Constance Green and Milton Lomask say that Vangaurd 1 is the “the progenitor of all American space exploration today”. It wasn’t just the satellite, it was the support systems too, such as the tracking network hosted by multiple nations.

It was Soviet leader Nikita Krushschev who called Vanguard 1 the “grapefruit satellite”, and he didn’t mean it as a compliment. But funnily enough, after satellites weighing thousands of kilograms and the size of double-decker buses, the current trend is back to small satellites.

Rather than fruit, these satellites are likened to loaves of bread or washing machines. They’re cheap to build, with off-the-shelf components, and cheap to launch. They’re not meant to stay in orbit for centuries. They’ll do their job for a few months or years, and then self-immolate in the atmosphere.

There has been a long tradition of amateur satellites, but now space is more accessible than ever before. Students and space start-ups can get into orbit at a fraction of the cost it used to take. It’s revitalising the space economy and allowing a greater number of people to participate.

For example, QB50 is an international collaboration to launch 50 cubesats to explore the lower thermosphere. So far, 36 have been launched, including three from Australia last year.

Elon Musk’s SpaceX company is planning to launch a network of more than 7,500 small satellites over the next few years, to deliver broadband internet. (There are major concerns about how they will contribute to the space junk problem, however).

When Vanguard 1 was launched, its only companions were Explorer 1 and Sputnik 2. Soon it may have thousands of descendants swarming around it.

The little satellite meant to represent the peaceful uses of outer space is a physical reminder of the competition to imprint space with meaning in the early years of the Space Age. Now, 60 years on, it seems we are on the cusp of a new age in space.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Dr Alice Gorman is an internationally recognised leader in the field of space archaeology. She is a Senior Lecturer in the College of Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences at Flinders University, where she teaches the Archaeology of Modern Society.

Her research focuses on the archaeology and heritage of space exploration, including space junk, planetary landing sites, off-earth mining, rocket launch pads and antennas.

She is a member of the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics, the Advisory Council of the Space Industry Association of Australia and the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies.

Her articles have been selected four times for The Best Australian Science Writing anthology, and 2017 she won the Bragg Prize in Science Writing.

She tweets as @drspacejunk and blogs at Space Age Archaeology.

She is a member of the Editorial Board of The Journal of Toaster Studies.